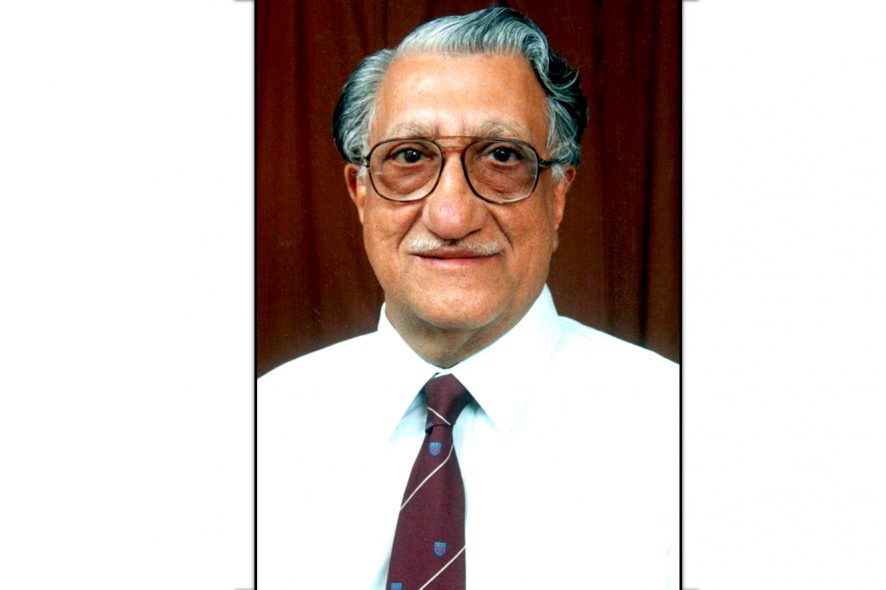

Anil Divan completed his innings on 20-3-2017, few months short of 87. He was one of the most respected constitutional experts and known to the bar and the bench as an upright lawyer, who did not bend the rules of professional ethics and principles, to suit the circumstance. As Rumpole, the fictional Old Bailey lawyer created by John Mortimer and one of Divan’s favourite characters, said when he was advised to move with the times, “If I don’t like the way the times are moving, I shall refuse to accompany them.”

My association with Anil Divan began in the year 2000, when I joined his chamber as his Junior, and continued till his last day. In the initial months, I was quite at a loss, as briefs involving complex issues were being handled by him. It was also not easy for a then raw junior to overcome his towering and sometimes intimidating personality and risk a display of his well-known temper. One Sunday morning, I remember knocking on his door — a young lawyer fresh out of law school talking to a stalwart of the Bar — and asking him to suggest some books that I should read. From my side, this was designed to be a conversational gambit but I did not know then that he was not given to idle talk. His brusque response — “Read whatever you like, there are so many books lying on my library shelves” — sent me on a quick retreat back to my desk. A few moments later, however, Divan stepped out of his chamber and said to me, “As a young lawyer you must read books on ethics like Professional Conduct and Advocacy by K.V. Krishnaswami Iyer and autobiographies of legal luminaries who have set high professional standards.”

My understanding of the law and the legal system as well as the deep-seated appreciation of the importance of ethical standards in legal practice, I owe to Divan. In my letter congratulating Divan, on completing 65 years of practice, I wrote “In my practice and even otherwise, whenever I am in doubt, I ask myself what my Senior would have done in a situation like this and the answer to this question guides my choice, invariably in the right direction.”

Anil Divan strongly advocated the belief that success at the Bar is no success unless achieved by adhering to the highest standards of professional ethics. There were certain absolute non-negotiables for him — clients, no matter how powerful or rich, had to visit his chamber with their case and fees were never accepted in cash. A partner of a solicitor firm recounted to me an instance (later confirmed by Divan) when Divan, who was engaged to appear for the son of a sitting Prime Minister, was requested to visit the PM’s residence to discuss the case. Divan was quick to remind the solicitor that the PM, in this circumstance happened to be his client and would therefore need to meet him — like all other clients — in his chamber! A seasoned politician, who engaged Divan in a proceeding before the Election Commission, sent his entire fees in cash to Divan’s chamber, in return for which he got an earful, notwithstanding his standing as a politician. The poor politician later told me that this was the first time he was having to pay a lawyer’s fee by cheque. Not only did Divan never appear before a court without full preparation, he also did not tolerate a junior who came to brief him without mastering the case. Arun Jaitley, speaking on the occasion of Anil Divan’s 50 years at the Bar, described how as a junior counsel briefing Divan, he would never enter Divan’s chamber unless he knew the brief backwards.

Anil Divan stood for probity in public life. His greatest contribution came in the form of the judgment in Vineet Narain case[1], 1998 (also known as Jain Hawala case), which he fought pro bono. In this case, the Supreme Court struck down the Single Directive, an executive order which required CBI to take prior approval of the Head of the Department before commencing any investigation against an officer above the rank of Joint Secretary. In 2003, the DSPE Act, 1946 was amended, in effect reviving the Single Directive — this time through legislation. The amendment was challenged and the Constitution Bench[2], on the basis of Divan’s arguments, unanimously struck down the amendment. While Jain Hawala case1 was going on, in 1996, Divan came to know that Mr Ram Jethmalani has agreed to appear for Shri L.K. Advani, who was one of the accused in Jain Hawala case1. The petition in Jain Hawala case1 was originally settled by Jethmalani, and his subsequent appearing for Advani was, according to Divan, improper. He issued a press statement “…, if petitioner’s counsel or those in similar position appear for any of the accused, lawyers as a class and the integrity and independence of the legal profession and legal process would diminish in the eyes of the public”. Divan did not mince words, while speaking up in favour of upholding high professional standards, even if it meant speaking against a close friend.

In later years, Divan conducted Black Money case[3], pro bono for Jethmalani, in which the Supreme Court appointed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) consisting of retired Supreme Court Judges to look into the issue of black money and undisclosed foreign accounts.

His death has left a vacuum, particularly for public interest litigators and NGOs, who knew that there was a General in waiting to lead them from the front in the battlefields, if he saw a public cause in an issue brought before him.

Anil Divan had been writing extensively on judicial appointment by the Collegium — which he felt required extensive reform, without impairing the independence of the judiciary. Divan was however critical of the NJAC Act and the 99th Amendment. He called it “a poisoned chalice, an ill-conceived wolf in sheep’s clothing”. The Amendment and the Act were successfully challenged† by the Bar Associations that were led by Fali Nariman and Anil Divan.

Cricket was his other passion. He called his collection of writings On the Front Foot, a title that indicated his love for the game as well as his stand on the issues that he took up. In his young days, Divan was an ace badminton and tennis player. When asthma cut short his time on the badminton and tennis courts, he took to golf and developed a very good handicap. He was a regular at the greens till last year and it was well known amongst briefing lawyers that he never changed his golf schedule to accommodate conferences, often emphasising — “nothing comes between me and golf”.

Mr Divan had returned from a holiday in Goa on Sunday. In his last telephonic conversation with me, he had instructed me to not take up any work on Monday as he wanted to get ready for the final arguments in the Cauvery†† appeals before the Supreme Court. Fate had some other design. On several occasions, I heard Mr Divan extolling the virtues of “dying in harness” and I think none would have been more satisfied than him with the manner in which death came to him — with a full day of work marked out on his calendar and with his beloved family at his side in his last moments. He had issued clear instructions that should he fall terminally ill, he should not be put on life support — “I have lived with dignity and will die with dignity.” And so he did.

[1] Vineet Narain v. Union of India, (1998) 1 SCC 226

[2] Subramanian Swamy v. CBI, (2014) 8 SCC 682

[3] Ram Jethmalani v. Union of India, (2011) 8 SCC 1

† Ed.: The reference seems to be to Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Assn. v. Union of India, (2016) 5 SCC 1

†† Ed.: The reference seems to be to State of Karnataka v. State of T.N., Civil Appeals No. 2453 of 2007 with Nos. 2454 and 2456 of 2007