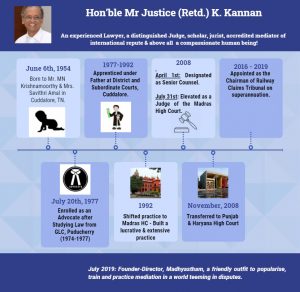

Justice Kannan Krishnamoorthy was born to Mr M.N. Krishnamoorthy [fondly known as “MNK” who was the “Sir Alladi” of the Cuddalore (a district in Tamil Nadu) Bar] and Mrs Savithri Ammal, in 1954. He pursued Economics from the renowned Loyola College, Chennai and then graduated Law from the Government Law College at Pondicherry, in 1977 and enrolled in the Bar in the same year. He spent his initial days of apprenticeship with his father and then built a formidable practice on civil side. Until 1992, Justice Kannan practised extensively before the District Courts in Cuddalore and thereafter he shifted his practice to the Madras High Court. Sixteen years later in April 2008 Mr Kannan was designated as a “Senior Counsel”. Fortunes smiled again in 2008 when Mr Kannan was invited to accept judgeship at the Madras High Court, and assumed charge on 31-7-2008. In November of the same year, Your Lordship was transferred to the Punjab and Haryana High Court and after a circa decade’s stint there, Justice Kannan retired on 5-6-2016. Justice Kannan thereafter was appointed as the Chairperson of the National Railway Claims Tribunal’s Principal Bench in New Delhi, a term which lasted for three years. In 2019, he founded Madhyasatham, a friendly outfit to popularise, train and practise mediation. Reading Justice Kannan’s judgments one comes across “a jurist endowed with a legislator’s wisdom, historian’s search for truth….” [Quote taken from Justice K. Ramaswamy’s autobiography, Ceaseless and Relentless Journey, Eastern Book Company (2008)]. To quote a scholar, who was asked to introduce Justice Kannan, “On Bench, Justice Kannan’s justice-ing has been justice of law, justice of fairness, justice of pragmatism, justice with intellectual depth and above all justice from His Lordship’s heart.”

The interviewer, Mr Ujjwal Jain is a Student Ambassador for EBC-SCC Online and is currently pursuing law from Tamil Nadu National Law University, Trichy.

This is a two-series interview. The first series covers early life and practice of the interviewee and passes the baton to the second series, which graduates to cover his experience as a judicial officer of the High Court and as a mediator.

Part A: Early life and practice

“Mr K. Kannan is the chip of the old block, late Mr M.N. Krishnamoorthy Ayyar of Cuddalore Bar, the local alladi who completed 61 years of practice of law at the district and other courts of South Arcot District of yonder years early in 1999….”

Born to Mr (late) M.N. Krishnamoorthy, a leading practitioner in the Cuddalore District, Justice Kannan also inherited the legacy and blessings of his maternal grandfather (late) Mr Krishna Iyer, who was famously known as “law point Krishna Iyer” and headed a large team of lawyers and juniors.

- When contemplating career options in your early days, was law an obvious choice, considering the fact that none of your seven siblings took law as a career?

I had not thought about it till my father told me as soon as I finished my intermediate exam that I should take to law. My first two brothers were engineers and the third one, a doctor, while my sisters were home makers. I fancied myself to be a writer of novels and poetry. The closest to getting to do this was law, where I could script plaints that was a bit like storytelling and even use idioms and metaphors in pleadings like in poetry.

“MNK was a hard taskmaster … known to be tough man who would not relent from his point easily, particularly at the art of cross-examination which would be a delight to watch, based as it would be on long hours of meticulous preparation.”

“A good senior can make all the difference to the career of a young lawyer.” (Sorabjee & Datar, Nani Palkhivala: The Courtroom Genius).

2. Please do take our readers back to your days of apprenticeship and share with us some of your profound experiences under your senior as well as practice in the subordinate and District Courts of Cuddalore.

My father was a hard worker, made several drafts of pleadings before he settled on the final version, prepared meticulously for cross-examination and executed with laborious acumen. He believed that there could be a legal precedent to any situation that you want to fit in to your case but he would not cite it unless he found the judgment to pass through his own test of fairness. He argued with immense commitment to his client’s cause and suffered no mean statement about his case from his opponents or even from Judges. Even during my college days, I used to take down dictation along with the stenotypist and joined typewriting class to pick up speed. In the initial phase of my practice, he would correct even short replies or objections that I prepared and in about 3-4 years, I had understood his style and trusted my drafting. He would sit in the court where I argued and give critical comments about my presentation later at the dinner time. He found me far too short in my arguments. He would never be satisfied with my reading a provision of law in court; he would want me to use my own illustrations to explain a statutory provision if there was no statutory illustration. I could not merely use headnotes of decisions in court. He would insist that I paraphrase the facts of the case before setting out the law from the text of the judgment. My mother never accepted any criticism that he mounted about my performance and would come passionately to my support.

Fresh law graduates aspiring to build a career in litigation are often advised to edifice their career on few years’ practice at civil courts and criminal courts, before taking up specialisation.

- What is your advice to a fresh graduate on: (a) early years of practice in subordinate courts; and (b) specialisation?

Sir, you spent one-and-a-half decades practising both civil and criminal law at the subordinate and District Courts at Cuddalore. In your considered opinion, was this experience instrumental in ensuring their professional success at the Bar?

My practice in subordinate courts in a mofussil area was a Hobson’s choice, because that was where my father practised. Sometimes, clients from distant places would camp with their families in our house at the backyard for a whole week or a fortnight when the trial was in progress. Trial work was by default on a day-to-day basis. No case would be prepared in a hurry or without understanding all the facets of the case. I used to know all the village registers and the way a Village Administrative Officer maintained his records; understood the working of the Revenue Division of the district and cultivated the methodical way of eliciting facts and gathering documentary proof for preparation of pleadings. Traditionally, my grandfather and father had been on the civil side and hence my bulk of practice was in civil courts. I accepted briefs in all forums, before Registrar of the Registration Department, before the District Revenue Officer, before the Land Reforms Tribunals and toured all through the district and appeared before all courts. My foray with criminal practice was essentially legal aid appearances for indigent accused that sharpened my forensic skills of cross-examination. Once, I remember that a doctor who had performed a post-mortem, had, by mistake, referred to particular wound in the brain matter with the corresponding injury on the skull as having caused the death. When it became clear in the cross-examination that the wound was a surgical wound performed by the doctor to drain the extravasation of blood in the head caused by a blow with a club, the accused was acquitted. It was a thrilling moment to secure an acquittal in a Section 302 trial with less than 3 years of practice.

Trial work is necessary to understand litigation and it is essential to be a generalist in practice and take at least 5 years’ time to take to an area of specialisation. I found it to be enriching experience to watch trials when senior lawyers were cross-examining witnesses. After 10 years of practice, I set up a study circle at the local Bar, with a senior lawyer invited to lecture on a topic of practical importance for 20 minutes, some junior lawyer gathering data of reported cases and reading them out in 20 minutes, and collecting a handful of doubts from lawyers in a box which will be read out one after another and invite yet senior lawyer to answer them in 20 minutes. I have little doubt that these sessions imparted large learning possible for me that remained in good stead in later day practice.

Part B: 16 years’ illustrious and eventful journey at the Madras High Court

Advocate – Senior Advocate – Judge

“The ground work put in by him (Justice K. Kannan) as original, trial and appellate lawyer in the mofussil district headquarters was tamed on his moving to the metropolis, then was trimmed and was continuously polished and his efforts got revealed when he started to write regularly and week after week as editor — all of which have helped him to reach the peak which every entrant in our profession aspires to climb from day one.

4. If you could please narrate your experience in the early years of practice i.e. after shifting to the Madras High Court?

Even as I was new to Madras High Court, I was not new to practice. By 15 years of hard work, I had earned clients from 3-4 districts. Having practised in trial courts, I knew where to gather the data from, that is, from the stage when court endorsements of returns were made to the court notings in the dockets, even apart from pleadings and documents filed. I would look at a Judge squarely while arguing, with both my legs firmly on ground and distributing the weight of the body and carrying no slouch. I spoke, perhaps, a little fast, to cover up a stutter that I had, but I had a clear diction that earned the attention of all courts. I read judgments of the High Court seriously and wrote critiques on judgments on a regular basis in law journals. I discussed law at all places where lawyers could be found and spent considerable time at the Bar library during my free time. I took active part in judicial academy to share knowledge with trainee Judges. As a trial lawyer, I dealt with lots of cases on testamentary and intestate succession. Compensation law for accident injuries captured my interest for the ineffable sufferings that indigent people suffered in pursuing their claims through some unscrupulous practitioners. I read and wrote on “wills and succession”, “accidents and compensation” and “landlord and tenant” and coedited a popular book on “Indian Succession Act” along with one of the most prolific Judges of the High Court, S.S. Subramani, J., who had retired from the High Court and a Vice Chairman of Central Administrative Tribunal , and undertook independently the editing work of Sarkar’s Specific Relief Act and MLJ’s Commentary of Motor Vehicles Act along with a lawyer friend, N. Vijayaraghavan, who knew the last word on Motor Vehicles Act and the law of insurance. There is no better way of improving the field of law of your practice than writing a book on the subject. That is when you really understand the law and incidentally gets you to be noticed.

“The vanishing books are not merely from court halls. They are happening also in lawyer’s offices and chambers. The blighted Lilliputian CDs shrink a whole tall rows and columns of shelves that hold the books to a millimetre thick circular wonder. From the senior who could brag about his memory and pull out the book from the wooden bureau, he is subordinated to a minor role pitifully, when he is constrained to urge his own junior to locate the case law from the internet or the CD.” (2007) 5 MLJ 129

The advent of computerisation and digitalisation has brought premium legal databases like “SCC Online”, thus, making far-reaching changes in modus operandi of legal research. It would not be an exaggeration to state how wings are to a bird; SCC Online is to a legal researcher. But the same was not the status quo ante in substantial years of your practice at the Bar and you have witnessed the entire transition from pre-computerisation to CD form of database to SCC Online as it is today.

5. In this backdrop, how did you undertake and master the art of legal research in the pre-computerisation era? Also, please do share your experience in the entire transition from pre-computerisation to what online legal researching has become today.

My father would keep an “authority notebook” and he would note all the case laws that he would gather while preparing for arguments for a case. The practice was not lost to me and I began to gather case laws on a regular basis. On a visit to France to my sister’s place, I saw the use of personal computers in office and got myself a desktop and took interest in developing software skills in late 1980s. I wrote programs on FoxPro for creating a caselaw digest and called it CADS with the assistance of a client, who had a child custody case with me and who was a software expert. Cases drawn from weekly law journals were entered systematically and I would have on striking the “enter” key (windows and mouse were not yet in), display on screen the required citations and case notes. There was enough hoopla around my work with computers and a ring of wonderment as though computers produced case laws. I have even received a request from a District Judge asking me in court whether my computer had an answer to a knotty legal problem that he encountered in a case before him.

- If you could please narrate about any fond memories from the day when they were conferred with the “senior advocate” designation? Also, request you to throw some light on the “senior advocate” designation process back then.

I was a senior advocate after 31 years of practice and no great achievement. I did not desire it since I never had a practice of engaging a senior counsel and any client either wanted me or he would seek for himself a senior. I was engaged as senior in civil appeals and revision petitions. However, when my partner in practice and younger to me in age, was designated as a senior counsel, about which I came to know only post the conferment, there was a kind of peer pressure that I also became one. The Chief Judge’s acquaintance with a lawyer made a difference and if he had a Bench partner, who was a former chamber mate, as I had, things moved easily. Though a collective Full Court decision, the Chief Judge called the shots and at the time, when my candidature for conferment was put up before the Full Court, the Chief Judge was reported to have remarked that the collegium had thought fit enough to recommend my name for judgeship and there ought not to be a problem doubting my competence to be a senior counsel.

- In July this year, the Madras High Court notified “The Madras High Court Designation of Senior Advocates Rules, 2020”. Pursuant to the said Rules a 5-member “Permanent Committee for Designation of Senior Advocates” has been constituted. The said Committee consists of the Chief Justice along with two senior-most Judges of the Madras High Court, the Advocate General for Tamil Nadu and a designated senior advocate selected by the members of the Permanent Committee from the Bar. This Permanent Committee replaces the previously formed 10 Judges Select Committee under the 2014 Norms. The Bar Council of India (BCI) in its letter addressed to the Chief Justice of Madras High Court and Companion Judges, has requested the latter to recall the aforesaid Rules. Inter alia, the BCI raised the concern about the presence of the two non-judicial members in the Permanent Committee and is of the belief that such an arrangement runs contrary to the statutory mandate of Section 16(2) of the Advocates Act, 1961. In your considered opinion, is it appropriate to involve the non-judicial members in the process of designation?

If eminence in law and fairness in presentation are the hallmarks of senior counsel, why should judging the qualities of a senior counsel, why should the judgment rest on the shoulders of only judicial personnel? Why not non-judicial members? Anyway, the propensity to please judicial members, when in a group, could always be noticed and the judicial members will never lose their primacy to have their views executed.

“This is my father’s birth centenary year. I trained under him as a lawyer. I could never have given him greater pride than my judgeship. Sixteen years back, when I left Cuddalore for Chennai, my mother wrote to me an inland letter. She did not post it but delivered it by her own hand (I still have it) that one day, I would be a High Court Judge. Only a mother could have such an outlandish idea, at that time, on account of love for her son, but surprisingly, her love has placed me here at this podium.”

– Your Lordship, Justice K. Kannan, swearing-in ceremony, 31-7-2008 (Chennai) in the august presence of the then Chief Justice of Madras High Court, Justice A.K. Ganguly.

Times flowered and providence will in 2008 – the year when your mother Mrs Savithri Ammal’s Midas words came true – the year, when fortunes smiled twice: the first time when you were designated as a “Senior Counsel”, and again when you received an invitation from the Bench to accept judgeship.

8. If you could reminisce and narrate the trip down the memory lane to those moments when you were offered the coveted judgeship of the Madras High Court? Were there any second thoughts on the acceptance of the same?

Six years earlier to when I actually became a Judge, my name was under reckoning but there was political opposition to my candidature. Again, when my name propped up, there was opposition from the ruling party. The compromise formula seemed to take me in but post me outside the State. When I heard about it, I was slightly disappointed and did not want to move away. Jharkhand or Punjab and Haryana seemed the prospects. I had a cousin who was in the administrative service, having served in Chandigarh he said, a stint of life in Punjab would make me a fuller person. I was a way outsider, having arrived relatively late at the High Court. I was happy to accept it and was a relief from the litigation scene, which I did not enjoy as much. I was looking to break free from adversarial litigation to mediation. I genuinely believed that I could be of greater influence in promoting mediation as a Judge involved in policymaking than as a lawyer.

“A famous lawyer, without a learned senior is a rarity … Stop any senior lawyer and ask him about his senior. Even the most reticent or reserved types among the seniors would reminisce fondly about their revered seniors, turn misty-eyed and slip to wordy cascade of appreciation and the great times they had and invariably conclude, andhanalmeendumvaradhu – (such like times will not come again).” (2007) 6 MLJ – Civil, “guru-shishya parampara”

What should young advocates keep in their mind when contemplating which senior’s office should they join in initial years of practice?

The senior shall be known for his sterling qualities of hard work and ethical practice. A successful lawyer is not necessarily a person who has a large bungalow and a swanky car. A trial lawyer is most ideal. There shall be no hurry to come to city for practice at the High Court. Mofussil courts are good training grounds. There is enough work to do at the districts. During law college days, students get to visiting courts. Spot the lawyers who are most talked about in courts as the good ones; the lawyers who are respected by Judges; lawyers who are known to entrust work to juniors with confidence.

“Today’s lawyers will be snapping the umbilical cord that sustains the dignity of the profession, if we break away from this (guru-shishya parampara) tradition …We need to realise that the tradition assures to us respect from the community, reinforces our beliefs in the nobility of the profession and encourages us to carry our learning lightly on our shoulders and with dignity.”

(2007) 6 MLJ – Civil, “guru-shishya parampara”

10. In your considered opinion, what vests on the shoulders of young advocates to ensure that the tradition of guru-shishya parampara is alive, practised in letter and spirit and safely bequeathed to our posterity?

In every busy lawyer’s office, there is bound to be hierarchical order of junior lawyers. It is good to recognise the flow of instructions from the entire line. If the lawyer is someone known to our family, it is ideal. 10 to 5 working hours’ mentality must be given up. Without being intrusive, the junior must be available at all the working hours of the senior at the office. Asking questions all the time is not the best way of learning. It is the lazy way. Go to textbooks. Find answers through judgments. Speak to your peer group. And finally arrive at the senior.

Read Part 2 of this informational interview HERE

*Due credits to Advocate Mr Amrith Bhargav for his kind help in this informational interview.

** Photo Credits: Weinstein International

[…] interview is Part 2 of the 2-part series. If you have missed reading the first part, click here to read the same on our […]