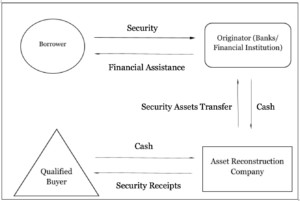

The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002 (hereinafter “SARFAESI Act”) was enacted as an urgent legislation to resurrect the dwindling financial sector, especially the one pertaining to the banking economy. Defaulting loans and escalating levels of non-performing assets of banks and financial institutions (FIs) led to the constitution of the “Narasimham Committee” and the “Andhyarujina Committee” by the Central Government for suggesting changes in the aforementioned sectors. The Committees essentially recommended enactment of a separate comprehensive umbrella legislation for ensuring security of financial assets and issue of security receipts (essentially loan borrowings, etc); reconstruction of secured assets; enforcement of security interests (i.e. recovery of outstanding loans, etc.) and other functions ancillary to the previous three. Accordingly, the SARFAESI Act, 2002 came into existence for ushering in an era of efficient or rapid recovery of non-performing assets (hereinafter “NPAs”) of the banks and FI. The process which was envisaged with respect to loan borrowings at the time of enactment of SARFAESI Act can be explained easily by way of the following flowchart:

“Security” refers to collateral immovable/movable property mortgaged with the bank/financial institution.

“Financial assistance” refers to loan borrowings or any kind of financial support.

“Asset reconstruction company” refers to an internally created unit of the bank/FI for evaluating the value of the stressed assets and ensuring that reconstruction in a way to ensure that they are sold off for recovery of the outstanding loan amount/borrowings to the borrower.

“Security receipts” refer to reconstructed immovable or movable property mortgaged with the bank/FI.

This article analyses the concept of “continuing cause of action” under Section 13(4) of the SARFAESI Act and the limitation available for challenging the said measures under Section 17 before the Debts Recovery Tribunal (hereinafter “DRT”). The concept of “continuing cause of action” implies that if multiple causes of action arise during any civil proceeding, then the period of limitation must be counted from the last and the latest action in point of time or till the proceedings initiated under any enactment are in existence.

Before proceeding ahead, it would be worthwhile to quote certain provisions of the SARFAESI Act, which shall be sheet anchor of the present article.

-

- 13. Enforcement of security interest.—

***

(2) Where any borrower, who is under a liability to a secured creditor under a security agreement, makes any default in repayment of secured debt or any instalment thereof, and his account in respect of such debt is classified by the secured creditor as non-performing asset, then, the secured creditor may require the borrower by notice in writing to discharge in full his liabilities to the secured creditor within sixty days from the date of notice failing which the secured creditor shall be entitled to exercise all or any of the rights under sub-section (4):

Provided that—

(i) the requirement of classification of secured debt as non-performing asset under this sub-section shall not apply to a borrower who has raised funds through issue of debt securities; and

(ii) in the event of default, the debenture trustee shall be entitled to enforce security interest in the same manner as provided under this section with such modifications as may be necessary and in accordance with the terms and conditions of security documents executed in favour of the debenture trustee;

***

(4) In case the borrower fails to discharge his liability in full within the period specified in sub-section (2), the secured creditor may take recourse to one or more of the following measures to recover his secured debt, namely:

(a) take possession of the secured assets of the borrower including the right to transfer by way of lease, assignment or sale for realising the secured asset;

(b) take over the management of the business of the borrower including the right to transfer by way of lease, assignment or sale for realising the secured asset:

Provided that the right to transfer by way of lease, assignment or sale shall be exercised only where the substantial part of the business of the borrower is held as security for the debt:

Provided further that where the management of whole of the business or part of the business is severable, the secured creditor shall take over the management of such business of the borrower which is relatable to the security for the debt;

(c) appoint any person (hereafter referred to as “the manager”), to manage the secured assets the possession of which has been taken over by the secured creditor;

(d) require at any time by notice in writing, any person who has acquired any of the secured assets from the borrower and from whom any money is due or may become due to the borrower, to pay the secured creditor, so much of the money as is sufficient to pay the secured debt.

***

-

- Application against measures to recover secured debts.—(1) Any person (including borrower) aggrieved by any of the measures referred to in sub-section (4) of Section 13 taken by the secured creditor or his authorised officer under this Chapter, may make an application along with such fee, as may be prescribed, to the Debts Recovery Tribunal having jurisdiction in the matter within forty-five days from the date on which such measure had been taken:

Provided that different fees may be prescribed for making the application by the borrower and the person other than the borrower.

***

(2) The Debts Recovery Tribunal shall consider whether any of the measures referred to in sub-section (4) of Section 13 taken by the secured creditor for enforcement of security are in accordance with the provisions of this Act and the rules made thereunder.

(3) If, the Debts Recovery Tribunal, after examining the facts and circumstances of the case and evidence produced by the parties, comes to the conclusion that any of the measures referred to in sub-section (4) of Section 13, taken by the secured creditor are not in accordance with the provisions of this Act and the rules made thereunder, and require restoration of the management or restoration of possession, of the secured assets to the borrower or other aggrieved person, it may, by order,—

(a) declare the recourse to any one or more measures referred to in sub-section (4) of Section 13 taken by the secured creditor as invalid;

(b) restore the possession of secured assets or management of secured assets to the borrower or such other aggrieved person, who has made an application under sub-section (1), as the case may be; and

(c) pass such other direction as it may consider appropriate and necessary in relation to any of the recourse taken by the secured creditor under sub-section (4) of Section 13.

Scheme of Sections 13 and 17

Under Section 13(4), after the accounts are being declared as NPA and the representation of the borrower/guarantor is rejected, the secured creditor (i.e. bank or FI) can take recourse to any of the measures specified therein to recover its outstanding debt. This includes taking over “symbolic possession” of the mortgaged property; or taking over the management of the business of the borrower, as mentioned thereunder. In continuum, Sections 13(5-A), (5-B) and (5-C) encapsulate the mechanism of auctioning of the mortgaged immovable property to 3rd parties for the recovery of the outstanding dues. If the statutory scheme is being seen holistically, then it clearly implies that taking over of symbolic possession followed by auction of the mortgaged property is all part of the same proceedings as a series of steps towards the larger objective of recovery of outstanding loan of the bank/FI. Section 13 is wide enough to allow the creditor to resort to any type of measures of recovery, and this is the distinctive feature of the SARFAESI Act, that it has vested the secured creditor with host of powers for arm-twisting the borrower or the guarantor for expeditious realisation of the outstanding borrowings.

Proceeding to Section 17, it employs the phrase “any person aggrieved by any of the measures under Section 13(4)”, which implies any and every action resorted to by the bank, it is authorised to take recourse to under and in pursuance of Sections 13(4), 14, 15, so on and so forth. The section does not clearly stop at providing remedy for the decision under Section 13(4), but transcends to include every such measure, which all are being undertaken by the bank towards making its action under Section 13(4) fruitful and consequential. The application under Section 17 is to be preferred within a period of 45 days “from the date on which such measure has been taken”. Thus, the concept of limitation running from the last and latest action in the series of continuing events with respect to recovery of dues from the borrower/guarantor concerned is duly embodied. Section 17 further acknowledges that the borrower/guarantor if aggrieved by the unlawful exercise of power by the lender authorities must not be left remediless and given time from every individual milestone of adverse action taken by the bank against him. Every subsequent milestone becomes and creates a fresh starting point for the aggrieved borrower/guarantor to approach the DRT by way of application under Section 17.

Pertinently currently existing Section 17 had been amended recently by Act No. 44 of 2016, wherein the previously available “right to appeal” or to “prefer an appeal” against the very same set of measures by the creditor came to be substituted with the word “application”. The reasons are not too far to seek for this intentful amendment to Section 17. Post amendment, the statutory position is clear that the DRT is the first stop forum for redressal of any aggrieved borrower, and widespread powers have been conferred on the DRT to undo the injustice or the wrong committed to the borrowers by the financial institutions in a desperate bid to recover their outstanding amount.

The Supreme Court in Indian Overseas Bank v. Ashok Saw Mill[1] interpreted the correlation between Sections 13(4) and 17 holding that the plethora of remedies and powers conferred under Section 17 acts as “checks and balances” on the creditors from misusing their powers. Section 17 balances the stringent powers of recovery of their dues vested with the banks/FIs and DRT can even restore possession after the same has been made over to the transferee by declaring any action under Section 13 as void. This includes setting aside any concluded sale transaction, even when the possession has been transferred to the auction purchaser. The Court referred to the judgment of Mardia Chemicals Ltd. v. Union of India[2] to hold that post the aforesaid judgment sweeping amendments were effected to Section 17, whereafter the DRT has been conferred with ample powers of restoring the position of the borrower back to its original place prior to Section 13(4) initiation. Vide paras 36-39, the Court held that the DRT if it discovers after inquiry that resort to Section 13(4) or any of its successive measures has been improper, then it can go to any extent and pass any order for restituting the borrower to its pre-Section 13(4) situation. This includes setting aside any transaction that might have happened including auction, sale, vesting of ownership in the auction purchaser, so on and so forth. Thus Section 17 is a repository of remedies and redressals available to any borrower against the bank and limited interpretation should not be accorded to it.

“Measures”, “Valuation of Relief” and “Continuity of Cause of Action”

Whether each and every action of the bank/FI taken against the borrower towards the recovery of its dues amounts to “measures”, or it is only the codified stages mentioned under Section 13 viz. declaration of the account as NPA; taking over of symbolic possession; or taking over the management of business to be termed as “measures”. The said question on interpretation of “measures” arose before the Division Bench of Telangana High Court in Durga Bhawani v. Canara Bank[3]. In the said case, the borrower approached the DRT challenging the first possession notice and the auction notice, which auction could not fructify. During the pendency of the application, a fresh auction notice came to be issued, the prayer challenging which was additionally incorporated by way of amendment as a subsequent event. However the DRT required the borrower to pay ad valorem fees of the outstanding amount afresh for incorporating a new prayer/relief challenging the auction notice as a separate cause of action. This order of DRT was challenged before the High Court as unsustainable and outside the purview of Section 17. Vide paras 7 and 8, the High Court held that a series of steps under Section 13(4) and in pursuance thereof taken by the bank amount to “measures”. The right of a person against whom these “measures” one after the other is being taken has a remedy available to challenge before the DRT and that it cannot be said that court fees becomes payable on every single successive individual cause of action. It further held that court fees before the DRT is never paid on the basis of independent valuation of each of the prayers made before it, but is payable on the application only once as a whole. Accordingly the condition imposed by the Tribunal requiring the borrower to pay court fees qua various “measures” challenged by it was set aside. The import of the judgment is that “measures” under Section 13(4) do not only constitute a continuing cause of action, but also have to be clubbed as part of the singular chain of events, intertwined and interlinked with each other.

Recently, the Division Bench of the Telangana High Court in Alpine Pharmaceuticals (P) Ltd. v. Andhra Bank[4] had an occasion to deal with the precise issue of the application under Section 17 being time barred having not been preferred within 45 days from the originally issued possession notice under Section 13(4), but only later within 45 days of a subsequently issued auction notice, issued much later subsequently in point of time. The bank contended before the High Court that since Section 17 application was not preferred in right earnest by the borrower challenging the initial possession notice under Section 13(4), therefore all the subsequent reliefs arising thereof become time barred and the prayer challenging the auction proceedings cannot be acceded to. The Court accordingly answered the specific issue on computation of limitation period of 45 days, when the borrower knocks at the doors of the DRT. Vide para 85, the Court held that cause of action starts when the “symbolic possession” is taken with the issuance of a notice under Section 13(4) triggering the availability of remedy under Section 17 before the DRT. However, even if the borrower did not choose to approach the DRT when he was dispossessed, but instead does the same when auction notice is issued later in pursuance of the same, then he cannot be non-suited on the ground that 45 days from the first cause of action [i.e. taking over of symbolic possession Section 13(4)] have expired. Vide paras 87-89, accordingly the High Court held that the limitation starts afresh everytime, whenever any new measure in the series is taken recourse to by the bank and 45 days have to be accordingly calculated from the last and latest measure. Somewhat similar view was also sounded in Indian Overseas Bank v. G.S. Rajashekaran[5] by the Division Bench of the Madras High Court. Vide paras 8-10, Court held that the cause of action continues till the various actions of the bank get concluded finally and DRT can be approached at any stage against any measure.

Conclusion

From the above discussion, it transpires that it is the dominus litis (master of the suit) of the borrower to decide the appropriate stage when he wants to knock at the doors of the DRT. Just because he challenges the auction proceedings at a later stage without agitating the validity of original notice under Section 13(4), does not debar him from getting his application considered under Section 17. The article therefore attempts to resolve the possibility of misinterpretation of Section 17 by any competent forum of law on this score.

†Advocate practising at Madhya Pradesh High Court and Supreme Court of India.

††4th year student of Dr Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow

[3] WP No. 12189 of 2018, dated 18-4-2018 .

[4] 2020 SCC OnLine TS 81 : (2020) 2 ALD 391.

[5] 2008 SCC OnLine Mad 1195 : (2008) 4 Mad LJ 1012.

Possession notice of DM challenged after delay of 15 days… condonation application dismissed on merits

But bank failed to take possession and gets fresh possession notice issued from DM

Whether now fresh SA again be filed?

Yes. The SARFAESI Act enjoins upon the lending institution to serve notice under section 13(4) for taking symbolic possession of the mortgaged property. Before taking physical possession, although it is not necessary to file section 14 application before the CMM/ DM, yet as a measure of abundant caution to avert any untoward incident by the property owner or anyone interested in property in any manner, it is suggested that an order from CMM/DM be obtained.

is it mandatory to give possession notice under section 13(4) of the act after demand notice under section 13(2) and before taking the assistance for possession under section 14 of the act?