Introduction

Over the last two years, the COVID-19 Pandemic has highlighted the pitfalls within the global health infrastructure. While the effects of the pandemic have been catastrophic for all, literature indicates that the impact on women jobs and livelihood has been disproportionately high.1 The ever-existing gender divide is further exacerbated when different manifestations of the disease are not tested on the threshold of sex and gender based immunological responses.

A study conducted in January 2022 by the Oregon Health and Science University reported that COVID-19 vaccines increased the duration of menstrual cycles among women.2 Although the effect was temporary in nature, it conclusively proved that the vaccines had a general adverse effect on the health of women, thus providing healthcare professionals the necessary information to counsel women about what to expect from COVID-19 vaccination for the first time. It is interesting to note that this study was conducted after a year of the vaccines being deployed and it only explored one specific side effect of the COVID-19 vaccine i.e. relating to the duration of menstrual cycles.3

Similarly, a recent report published by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy titled COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Women in Delhi closely examined the issue of vaccine hesitancy from a gendered lens.4 Following a survey of 1018 women to understand their perception of the COVID-19 vaccination and its uptake, it was found that 65.62% respondents were concerned about the risk of side effects from the vaccination. Further, 65.23% respondents also felt that the vaccine had not been adequately tested prior to its roll-out by the Government of India.

This low level of confidence in the efficacy of the vaccine and its impact on the health and well-being of the woman receiving it could have possibly stemmed from the lack of access to credible sources of information about the vaccination. While young women feared that the vaccination may disrupt their menstrual cycles, pregnant women grappled with the possibility of harm to the foetus.5

Pertinently, India did not allow the vaccination of pregnant women until July 2021,6 six months after the initial roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines, and the Operational Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination of Pregnant Women7 noted that the benefits of vaccinating pregnant women were greater than the possible risks that the vaccination posed to them. Since pregnant women did not form a part of the clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines,8 lack of safety data fuelled vaccine hesitancy among them.

The two studies and the nature and timing of the information provided by the Government of India is indicative of the long history of ignorance practised by the medical community towards the concerns of women as a group and their exposure to health risks. For a paradigm shift in the healthcare policies concerning both women and the society in general, female-centric healthcare measures are a necessary step. It is envisaged that the same would ease access to healthcare for women, thereby improving health outcomes for them. Additionally, since women are key stakeholders and influencers of overall health within the family structure, the informed decisions they make for the health of their family may potentially result in improvements to the healthcare system at large.9

Lack of data on gendered immunological responses

A woman’s body goes through a spectrum of experiences from a young age, starting with inter aliapre-pubescent effects, hormonal changes, onset of menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause. Further it has been documented that women are more susceptible to certain diseases such as cancer, osteoporosis and urinary tract infections as compared to their male counterparts.10 Despite the volume of factors that affect women and their health, there is a persistent lack of data mapping women health issues against various diseases.11 The COVID-19 vaccines and the corresponding lack of data on women immunological response to the vaccines is not an exception but an established practice within the medical industry, where specific risks regarding healthcare conditions of women are more often than not calculated with incomplete or limited data.12

Issue of information asymmetry and lack of agency

The lack of access to healthcare information is also closely tied to lack of education and digital literacy among women, contributing to information asymmetry. Even where relevant information pertaining to differential gendered responses exist, women access to such information is impeded due to multifarious factors such as socio-economic background, age, and educational qualifications. The Mobile Gender Gap Report, 2022 found that only 51% women in India are aware of mobile internet as opposed to 71% men. Limited purchasing power and lack of digital prowess therefore limit the ability of women to access relevant information on the internet.13

Further, women access to sexual and reproductive health also remains limited due to the lack of their autonomy over their bodies and marginal role in decision-making processes within the patriarchal set-up. In various societies, particularly in India, women have been conditioned to provide care and maintenance to the family unit, thereby making them promoters of overall family health.14 Owing to this stigma, women are often expected to remain silent about their health conditions and exhibit a higher threshold of patience for prioritising other family members.15 Formal education grants women greater chances of achieving financial independence and social stability which may coalesce into a higher degree of agency over matters concerning health and access to healthcare services.16

Way forward and recommendations

Moving forward, both the State and private agencies should aim to capture and aggregate data pertaining to women health conditions on an ongoing basis.

To ensure that active participation of women is maintained during the collection of data, women agency over bodily health and healthcare services ought to be enhanced by examining social factors such as discrimination, lack of agency and structural factors such as education, age, and financial status of women. Agency in terms of healthcare would mean enhancement of not only women access to affordable healthcare services but also their capacity to access reliable health-related information to minimise the information asymmetry prevalent within the system.

The data so collected may further be assessed to arrive at evidence-based action points on which structural change in the healthcare system can take place.

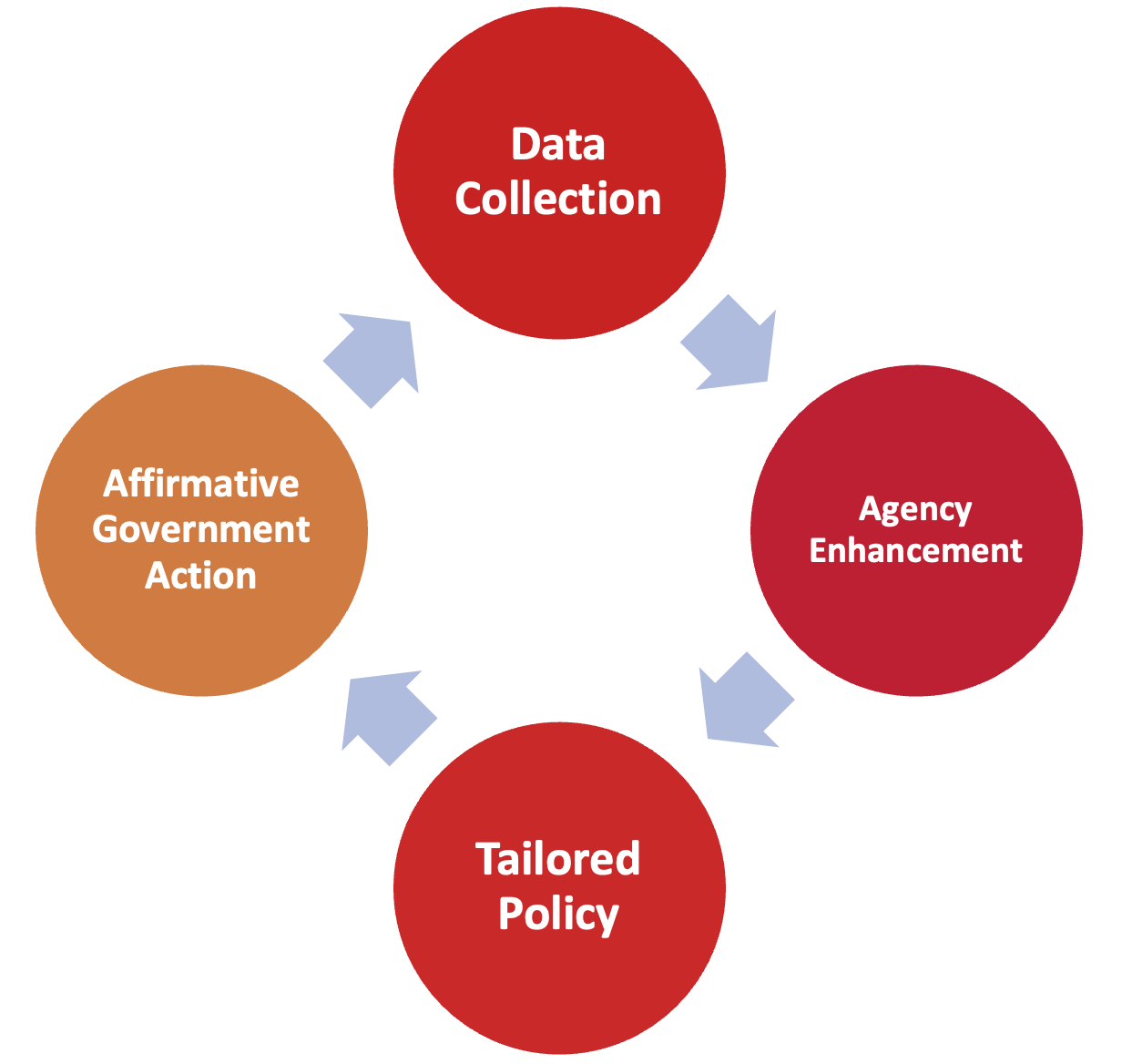

To activate this cycle of D-A-T-A i.e. Data Collection, Agency Enhancement, Tailoring of Policies and Affirmative Government Action, a conscious decision needs to be taken by both governmental and non-governmental bodies to examine health-related issues like the COVID-19 Pandemic from a gendered lens and arrive at policies which are evidence based and are tailored to the needs of specific groups in the society.

* Research Fellow (Legal Design and Regulation) at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Author can be reached at pragya.singh@vidhilegalpolicy.in.

** Research Fellow (Legal Design and Regulation) at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Author can be reached at lakshita.handa@vidhilegalpolicy.in.

1. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Women at the Core of the Fight Against COVID-19 Crisis (1-4-2020) <https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/women-at-the-core-of-the-fight-against-covid-19-crisis-553a8269/>.

2. National Institutes of Health, COVID-19 Vaccines Linked to Small Increase in Menstrual Cycle Length(25-1-2022) <https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/covid-19-vaccines-linked-small-increase-menstrual-cycle-length>.

3. Brian Alfred Boye, “COVID-19 Vaccine Launch in India”, UNICEFIndia (28-1-2021) <https://www.unicef.org/india/stories/covid-19-vaccine-launch-india>

4. Pragya Singh, Lakshita Handa, Husain Aanis Khan and Sunetra Ravindran, “COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Women in Delhi”, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy(8-11-2022) <https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/research/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-among-women-in-delhi/>.

5. Chinki Sinha, “Covid India: Women in Rural Bihar Hesitant to Take Vaccines”, BBC News (1-7-2021) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-57551345>.

6. Abhilash Gaur, “With Nod for Vaccine in Pregnancy, Crores of Families will Breathe Easy”, Times of India (29-6-2021) <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/with-nod-for-vaccine-in-pregnancy-crores-of-families-will-breathe-easy/articleshow/83941021.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst>.

7. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Operational Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination of Pregnant Women.

8. Astha Rajvanshi, “Why Pregnant Women in India Still are Not Eligible for COVID-19 Vaccines”, National Geographic (23-6-2021) <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/why-pregnant-women-in-india-still-are-not-eligible-for-covid-19-vaccines>.

9. A. Glynn, R. MacKenzie and T. Fitzgerald, “Taming Healthcare Costs: Promise and Pitfalls for Women’s Health”, Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 25(2) (1-2-2016) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4761820/>.

10. Medanta, “Cancer in India: Are Women More Affected than Men?” (29-4-2019) <https://www.medanta.org/patient-education-blog/cancer-in-india-are-women-more-affected-than-men/>; see also, K.A. Alswat, “Gender Disparities in Osteoporosis” (1-4-2017) Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, Vol. 9(5) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5380170/>; see also, Kim Huston, “Blame Your Anatomy: Women are More Prone to UTI than Men” (16-4-2018), Norton Healthcare, <https://nortonhealthcare.com/news/uti-ecare/>.

11. A. Holdcroft, “Gender Bias in Research: How does it Affect Evidence Based Medicine?”, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Vol. 100(1) (January 2007) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1761670/>

12. EO Kharbanda, J. Haapala, M. DeSilva, ‘Spontaneous Abortion Following COVID-19 Vaccination During Pregnancy’, JAMA Network, (8-9-2021), <https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2784193>.

13. Matthew Shanahan, The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2022, GSMA (June 2022) <https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-Report-2022.pdf>.

14. Paula Y. Goodwin, Dean A. Garrett, and Osman Galal, “Women and Family Health: The Role of Mothers in Promoting Family and Child Health”, International Journal of Global Health and Health Disparities, Vol. 4(1) (2005), <https://scholarworks.uni.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1023&context=ijghhd>.

15. Richa Jain Kalra, “Access to Health Care Difficult for Most Indian Women”, DW (21-8-2019) <https://www.dw.com/en/access-to-health-care-a-distant-dream-for-most-indian-women/a-50108512>.

16. Shibu John and Prerna Singh, “Female Education and Health: Effects of Social Determinants on Economic Growth and Development”, International Journal of Research Foundation of Hospital and Healthcare Administration (2017), Vol. 5(2) <https://www.jrfhha.com/doi/pdf/10.5005/jp-journals-10035-1081>.